Just One Tree’ is a blog series that explores how individual trees support life. Each post delves into the unique ecosystem centered around a single tree, showcasing its vital role in sustaining various forms of life.

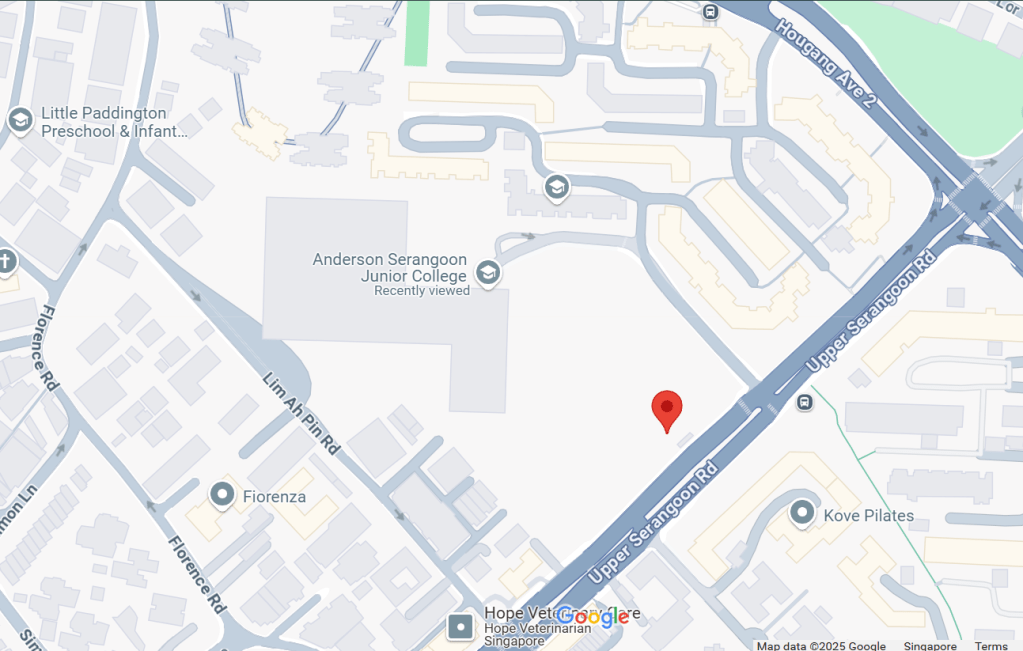

In this inaugural post of the series, I spotlight a particular tree along Upper Serangoon Road. I discovered this arboreal wonder while cycling to buy the famous Yong’s Teochew Kueh for my parents on the 9th January 2025. The tree stands within the vicinity of Anderson Serangoon Junior College (formerly Serangoon Junior College, where I studied for three months before transferring to Anderson Junior College in Ang Mo Kio in 1999).

What caught my attention was the tree’s unusual appearance – it was completely stripped of its leaves. My immediate reaction was one of concern and curiosity: What had happened to this tree?

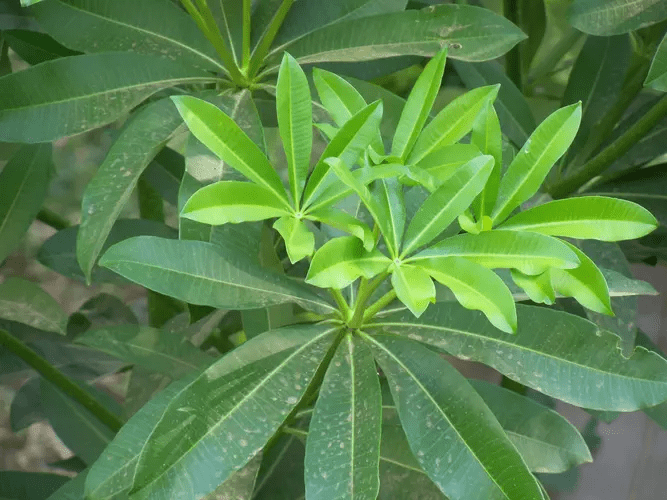

Upon closer observation, I noticed dangling aerial roots, a characteristic feature that left no doubt about its identity. This tree is a Ficus species, most likely a Ficus microcarpa, as it is one of the most common Ficus species grown in urban areas.

What’s Causing the Tree to Become Botak?

I parked my bicycle at the bus stop and approached the fence. Immediately, I found the answer: caterpillars! And not just any caterpillars, but Clear-Winged Tussock Moth (Perina nuda) caterpillars. Also known as the Banyan Tussock Moth, they weren’t just crawling all over the fence; they were also on the bus stop, the walkway shelter, and even on the ground.

As I was photographing them, one fell on my neck. I instinctively brushed it away in fright, worried that its bristles might cause an allergic reaction (fortunately, they didn’t).

Predators of the Caterpillars: A Search for Evidence

Having previously observed numerous cuckoos feasting on Phauda flammans caterpillars infesting a Ficus microcarpa in Jurong Lake Gardens, I hoped to see more cuckoos on this tree. I scanned closely for any fleeting movements against the bright afternoon sun. Instead of cuckoo-sized birds, I spotted two flycatchers darting around in their signature fly-catching moves, repeatedly returning to their ‘favorite’ perches after aerial forays.

Initially, I expected both to be common migrants – Asian Brown Flycatchers (Muscicapa dauurica). To my surprise, one of them has an orangey throat! It was a female Mugimaki Flycatcher (Ficedula mugimaki)! Interestingly, this uncommon visitor appeared very drowsy, frequently closing its eyes while perched on a branch.

Without photographic evidence of either flycatcher species feeding on the Clear-Winged Tussock Moths or their caterpillars, I couldn’t conclude whether these hairy caterpillars are part of their diet. This is in contrast to cuckoos, which have been documented feasting on Clear-Winged Tussock moths in my previous blog post. Nevertheless, I am quite positive that the flycatchers may be feeding on the smaller caterpillars or even the adult moths.

While photographing, an attendant, possibly ASRJC’s Operations Manager, approached and spoke with me. He shared his recent discovery of the infestation and mentioned that despite spraying copious amounts of pesticides, the caterpillars persisted. I suggested letting nature take its course, pointing out the presence of three insectivorous birds in the tree during our conversation as evidence of nature’s self-balancing mechanisms.

After capturing over a hundred photographs, I finally departed to purchase the Teochew kuehs. Just thinking about the Koo Chai Kueh (Teochew Chives Dumpling) is making my mouth water now.

Takeaway for Readers: Ficus – Nature’s Keystone Species

Ficus trees are commonly recognised as ‘keystone species’ – organisms that have a disproportionately large impact on their environment relative to their abundance. If removed, these trees can cause significant changes within the ecosystem. Given their elevated status in the ecological hierarchy, it’s always worthwhile to take a closer look at Ficus trees. By doing so, you’ll learn to appreciate how they support a diverse array of fauna species.

For wildlife photographers, learning to recognise different Ficus species can be immensely beneficial. These trees are often hotspots of biodiversity, attracting a wide variety of birds, mammals, and insects. By identifying Ficus trees in your area, you can increase your chances of capturing diverse wildlife interactions and behaviours. Whether you’re interested in photographing fruit-eating birds, nectar-feeding insects, insectivorous birds or even arboreal mammals, Ficus trees can serve as natural wildlife magnets, providing you with excellent photographic opportunities throughout the year.

Update: 24th March 2025

A wildlife enthusiast (Lui Nai Hui) just shared two photographs of a male Narcissus Flycatcher, Ficedula narcissina, spotted in Dairy Farm Nature Park) munching on a Stinging Nettle Slug, a caterpillar that has painful stings with venomous hairs.

These photo-evidences clearly demonstrate that Flycatchers, like cuckoos, can consume potentially venomous caterpillars. Based on this observation, I am confident that both the Asian Brown Flycatcher and the Mugimaki Flycatcher fed on the Clear-Winged Tussock Moth caterpillars infesting the tree.

Written by Lucas Teo