One evening, as you stroll along a quiet street, a distinct aroma catches your attention – a sweet floral scent fills the air. Without giving it much thought, you continue your walk. Suddenly, the sweet fragrance is replaced by a peppery, musty, and pungent odor that wafts through the night air.

Your mind briefly recalls old tales linking nighttime flower fragrances to supernatural presences. One such legend speaks of the frangipani scent associated with the Pontianak, a vampiric ghost of a beautiful woman who died during childbirth. According to folklore, when that sweet scent turns pungent, it signals that the Pontianak has become vengeful and is approaching fast.

A shiver runs down your spine, and goosebumps prickle across your skin. Your breathing quickens, and with each rapid inhale, the scent seems to intensify, filling your senses with its mysterious fragrance.

You remember some advice given from Russell Lee’s True Singapore Ghost Story Book – Do not look back or look up or you may see something you do not want to see, perhaps on the tree. Or some old wives’ tales – Do not shine your torchlight at the trees or else you may see the evil spirit and further aggravate it.

Tapping on Your Rationale Brain with Flora Knowledge

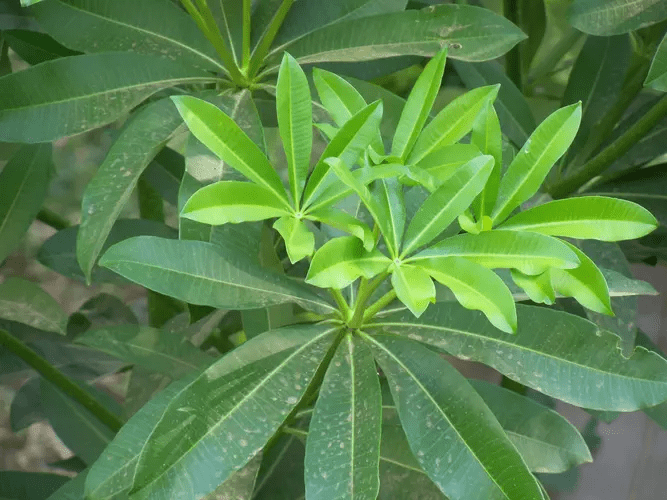

If you do have a torchlight with you and choose to disregard those warnings, you may spot clusters of tiny yellowish-green flowers on a few tall, sturdy trees nearby. This tree is the Alstonia scholaris, more commonly known as the Indian Pulai, and ominously referred to as the Devil Tree or Satan Tree, for reasons previously mentioned.

Should you retrace your steps, you’ll likely notice some Frangipani trees (Plumeria obtusa) in the vicinity, their fragrant flowers in full bloom.

The shift in scent is likely due to your proximity to two types of trees commonly found along pavements in housing estates and roadsides. Specifically, the overpowering fragrance of the Alstonia tree is probably the culprit, and you’re not alone in finding it overwhelming – many people share your aversion to its exceedingly pungent aroma. It is so smelly that a city in south-central Vietnam cut down over 3,000 trees (out of the 4,000 planted) in 2015 due to their overpowering and unpleasant smell, which has become unbearable for local residents (Click here for source).

In fact, the tree’s strong odour has led to some rather colourful nicknames. While we’ll refrain from mentioning the more crude monikers, it’s worth noting that the tree’s distinctive scent has certainly made an impression, inspiring a variety of descriptive (if not always flattering) names (You may refer to a reddit discussion on Alstonia Scholaris here)

Why Some Flowers Emit Strong Scent at Night?

You might still wonder, “Why is the scent so strong at night? It must be something supernatural?” The answer lies firmly in the realm of science, not the supernatural. Understanding nocturnal plant behaviour reveals a hidden world of ecological interactions that occur while most of us sleep.

Plant pollination takes on a different character after sunset, with specialised night-active insects and animals playing crucial roles. The strong nighttime fragrance isn’t a ghostly phenomenon – it’s a sophisticated biological mechanism.

Why do both the Plumeria and the Alstonia expend so much energy producing scents at night? After all, aren’t most butterflies and bees inactive during these hours? The answer lies in these trees’ fascinating relationship with nocturnal pollinators.

Some sphinx moths (also known as Hawkmoths), for instance, the Oleander Hawk Moth and the Yam Hawk Moth with their impressively long proboscises, are perfectly adapted to feed on and pollinate night-blooming flowers. (Note that not all hawk moths are nocturnal; some species, such as the hummingbird and pellucid hawk moths, are active during the day. Additionally, not all moths are pollinators, as some species lack a functional mouthpart for feeding, for instance, the Atlas Moth). These moths, along with certain species of bats, form a crucial link in the chain of nocturnal pollination. By releasing their potent fragrances after dark, the Plumeria and Alstonia trees have evolved to attract these nighttime visitors, ensuring their continued reproduction and survival.

These night-active pollinators are attracted to the strong scents and large, robust flowers of plants like Plumeria and Alstonia. While feeding on the nectar, they are also unintentionally transferring pollen from flower to flower, ensuring the plants’ reproduction.

Some Interesting Features of the Alstonia and Plumeria

The species name “scholaris” reflects the tree’s historical significance in education. Traditionally, its wood was used to craft slates for schoolchildren’s lessons, and it was also a preferred timber for making pencils. Interestingly, local lore suggests that the fragrance of the tree’s flowers had cognitive benefits, improving learning for those who sat beneath its branches. However, this notion is likely met with skepticism by many, as the scent of the flowers is often described as pungent and overpowering, rather than invigorating or conducive to learning.

There is another common name for the Alstonia tree i.e. saptaparni (in sanskrit), which literally means seven-leaves tree as the Alstonia’s leaves are held in clusters, usually adds up to 7. However, it is not always the case as botanically, it ranges from 4-8. For more interesting features of Alstonia Scholaris, click here to read more.

On the other hand, the Plumeria has deep cultural and historical roots, symbolising the exotic Oriental ‘East’ for centuries. This symbolism has been perpetuated in outdated tourism imagery, which often features bikini-clad, brown-skinned women adorned with frangipani flowers in their hair, reinforcing a problematic and stereotypical representation of tropical cultures. Ironically, the Frangipani actually originates from the tropical regions of South America – the ‘West’. For a more nuanced understanding of the Frangipani tree’s cultural and historical significance, click here for a recommended read.

Conclusion

The next time you catch a whiff of sweet fragrance, that suddenly turned pungent on a nighttime walk, remember – you’re not experiencing something supernatural, but rather witnessing an age-old dance between plants and their pollinators. This nocturnal plant behaviour, far from being ominous, is a testament to the incredible adaptability and ingenuity of nature.