Good-Evil, Hero -Villain, Cats-Snakes

A story from my primary school days, told by my Chinese Language teacher, etched in my memory and it went like this:

In a family home, a pet cat and a newborn baby coexisted peacefully. One day, a snake managed to slither into the house, posing a potential threat to the infant. The vigilant cat, sensing danger, confronted the snake. A fierce battle ensued, ending with the cat emerging victorious, having killed the snake to protect the baby.

With a sense of pride and accomplishment, the blood-stained feline approached its owners. However, the sight of their beloved pet with a bloodied mouth near their child’s room triggered an immediate and catastrophic assumption. Fearing the worst, they believed the cat had harmed their baby.

In a moment of panic and without verifying the situation, the owners struck a fatal blow to the cat. Only afterward did they discover the truth: their baby was unharmed, and a snake’s carcass lay nearby, revealing the cat’s heroic deed.

Overwhelmed with regret and sorrow, the family buried their loyal pet, now fully aware of its sacrifice.

As our teacher gently closed the book, a hush fell over the classroom. I remember the soft sounds of sniffling from my classmates as we grappled with the story’s emotional impact. In that poignant moment, I believe many of us developed a reflexive wariness towards snakes, our young minds associating them with danger and tragedy while linking domesticated dogs and cats as heroes.

Coincidentally, fast forward a few decades later in 2021, a viral story emerged that seemed straight out of a “Drama in Real Life” segment from Reader’s Digest. The story centred around a courageous cat named Arthur, who faced off against one of the world’s deadliest reptiles – the Eastern Brown Snake (Pseudonaja textilis). In a dramatic turn of events reminiscent of my childhood memories, Arthur’s bravery came at the ultimate cost. The feline hero sacrificed his life while protecting his family from the venomous intruder.

While the tale of Arthur’s bravery is undoubtedly touching, it’s worth considering an alternative viewpoint. As a proud owner of two rescued cats, I’ve observed that our feline friends’ actions might not always stem from a desire to protect us. Cats, by nature, are skilled predators with an instinctive drive to hunt. Their fascination with snakes often appears to be more about satisfying this innate urge rather than a conscious effort to safeguard their human companions. This predatory instinct, honed over millennia of evolution, compels cats to pursue and attempt to kill snakes and other small creatures.

However, it’s important to note that media portrayals tend to anthropomorphise animal behaviour, attributing human-like motivations to our pets’ actions. The narrative of a heroic cat sacrificing itself for its family is undeniably heartwarming and guaranteed to elicit an “aww” response from audiences. This emotional angle naturally leads to increased viewership and engagement.

These two narratives, whilst distinct, share a common thread: they cast cats and snakes into oversimplified roles of hero and villain. Such compelling yet reductive portrayals often fail to capture the true complexity of nature and animal behaviour. Consequently, they may inadvertently instill an unwarranted fear of snakes in people.

More alarmingly, these simplistic narratives can lead to celebratory reactions when snakes (villains) are killed, as evidenced by recent horrific incidents which happened in Singapore. In November 2024, two men was reported to have burnt a reticulated python to death, whilst in 2023, there was an incident of an individual decapitating another python while the crowd around him laughed and celebrated (see link). These shocking events underscore the dangerous consequences of perpetuating negative stereotypes about snakes and highlight the urgent need for better education and understanding of these often misunderstood creatures.

How Does Popular Culture Portray Snakes in Modern Society?

Snakes, also known as serpents in literary, mythological, or religious texts, have long held a significant place in human consciousness. Traditionally associated with evil and cunning, these reptiles have slithered their way from ancient myths to modern pop culture, often retaining their mysterious and sometimes sinister reputation. In many ancient traditions, snakes carried ominous connotations. The Biblical serpent in the Book of Genesis, portrayed as a crafty tempter in the Garden of Eden, led to humanity’s fall from grace. Greek mythology presents us with Medusa, a Gorgon whose hair of writhing snakes could turn onlookers to stone. These early depictions set a precedent for snakes as symbols of deceit, danger, and the darker aspects of nature.

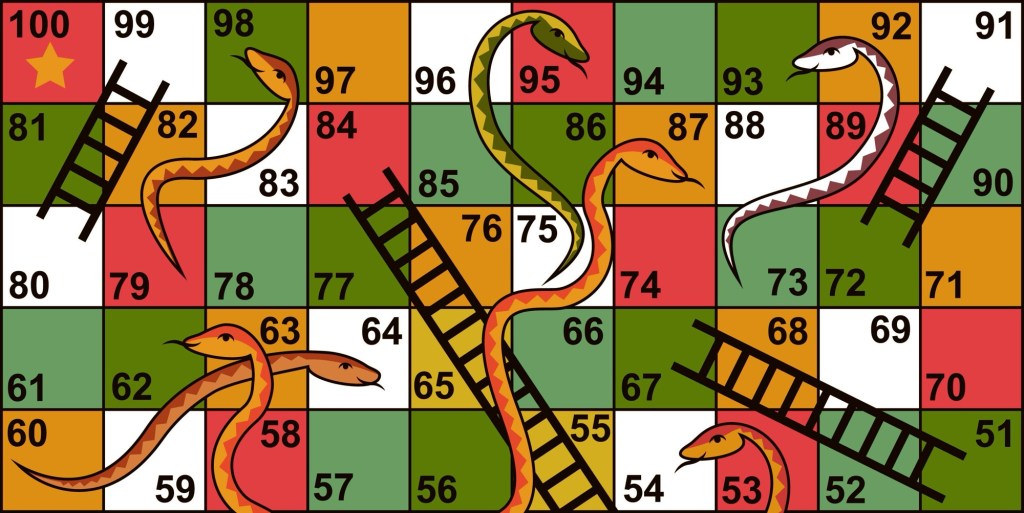

Snakes & Ladders

In a thought-provoking yet light-hearted sharing held on the 25th Jan 2025, Anbu, Co-CEO of Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES), pointed out that even seemingly harmless games like “Snakes and Ladders” can perpetuate negative perceptions of snakes. Who among us hasn’t dreaded landing on the snake in that classic board game? Building on Anbu’s insight, I couldn’t help but wonder: what’s implied when we land on that snake? Does it subtly suggest a snake’s supposed deadly appetite for humans, perhaps even the idea of being swallowed whole and… well, exiting through the snake’s other end? Anbu’s observation reminds us that even small, subtle details can profoundly shape our attitudes and biases.

Serpentine ‘Villains’: Snakes in Pop Culture’s Dark Side

Friendly heads-up for those unfamiliar with fantasy, comics and anime references!

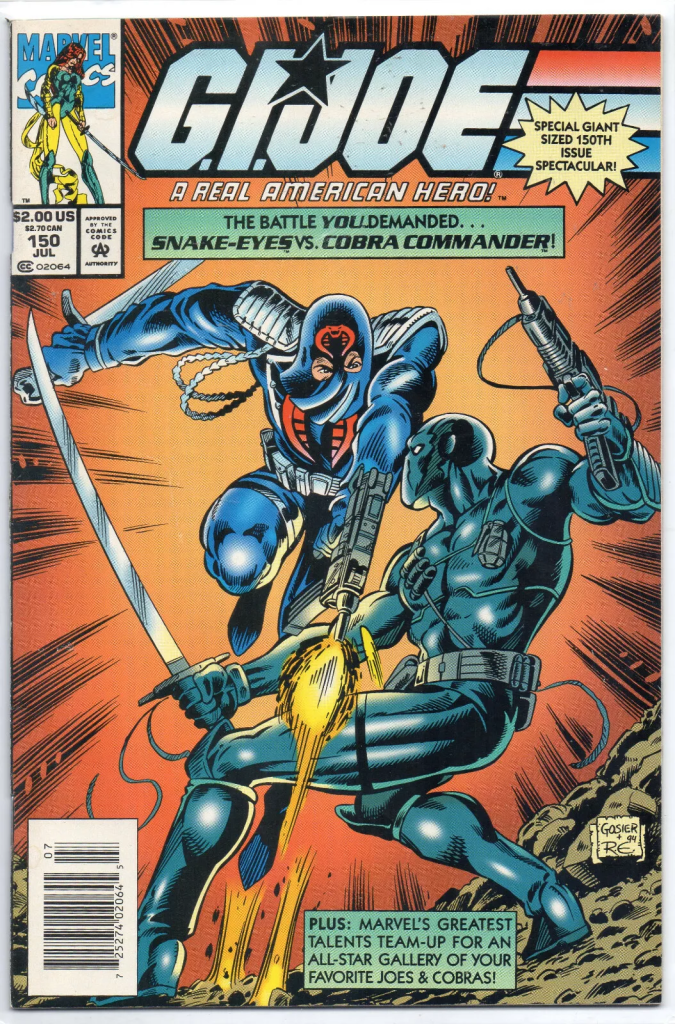

While often retaining elements of their traditional symbolism of darkness, modern interpretations have added layers of complexity to these serpentine figures. For instance, Cobra Commander, the primary antagonist of the G.I. Joe franchise, exemplifies the traditional portrayal of snakes as symbols of evil and cunning in popular culture. His iconic cobra-head helmet and the snake-themed imagery pervasive throughout his terrorist organisation, Cobra, reinforce this symbolism. Cobra Commander embodies qualities often associated with snakes: cunning, treachery, and danger, reflecting a longstanding trend in media where serpents represent villainy and threat. Yet, the G.I. Joe franchise also presents a contrasting snake-themed character: Snake Eyes. As a heroic ninja commando, Snake Eyes subverts the typical snake symbolism. Despite his serpentine moniker, he stands for loyalty, skill, and honour, fighting alongside the G.I. Joe team against Cobra’s terrorist activities. This juxtaposition within the same franchise highlights an evolution in the use of snake imagery in popular culture.

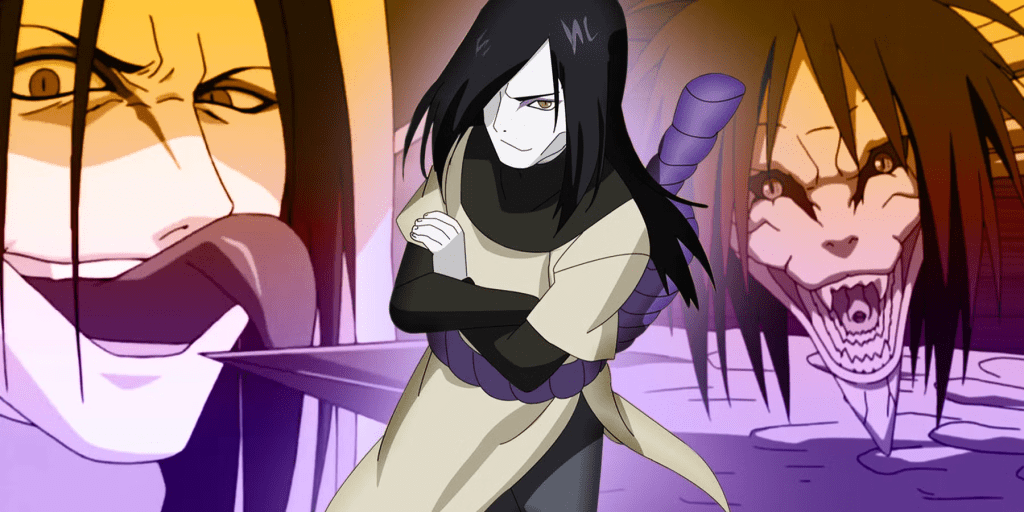

In the world of Japanese comics and animation, snakes continue to inspire intriguing characters. Orochimaru from the Naruto series, a human character closely associated with snakes, embodies the darker and more mysterious aspects of the ninja world. As one of the legendary Sannin, Orochimaru’s snake-like attributes reflect his cunning nature and forbidden jutsu, making him a complex antagonist. Despite his villainous past, he aided the protagonists by reanimating the previous Hokage, providing crucial support in the battle against Madara Uchiha and the Ten-Tails. This unexpected alliance showcased Orochimaru’s depth as a character, blurring the lines between hero and villain, and further cementing his status as one of the most memorable snake-inspired characters in anime history.

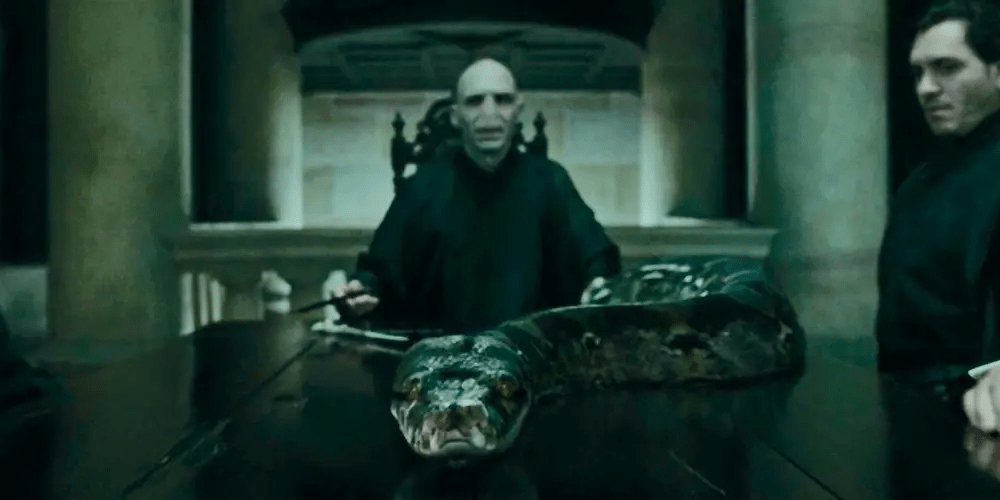

The Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling provides a multifaceted approach to snake symbolism. Slytherin House, one of the four houses at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, is often portrayed as the antagonist house. Its serpent symbol and reputation for producing dark wizards play into traditional snake symbolism. The series’ main antagonist, Lord Voldemort, is a descendant of Salazar Slytherin and a Parselmouth (able to speak to snakes). His connection to snakes, including his pet Nagini (later revealed as a Horcrux), reinforces his role as a dark and feared character.

While these modern interpretations often draw from traditional symbolism, they also add nuance. Characters like Orochimaru, Severus Snape and the Slytherin students are not simply evil, but complex individuals with their own motivations and redeeming qualities. This evolution in snake symbolism reflects a broader trend in storytelling towards more nuanced characters and a recognition that even traditionally “dark” symbols can have multiple interpretations. As our understanding of the natural world and our own psychology deepens, so too does our ability to create rich, multifaceted serpentine characters that slither beyond binary categorisations of good and evil.

When It’s Not All Dark & Dreadful… Yet Still Problematic

A familiar logo involving snakes can often be seen in Singapore, prominently displayed on emergency vehicles and uniforms. Whilst many recognise it, few may question its origin or significance. The Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF) refers to this emblem as “The Star of Life,” but our focus here is on the central element: the serpent-entwined staff known as “The Rod of Asclepius.”

The Rod of Asclepius, featuring a single serpent coiled around a staff, represents the Greek god Asclepius, a deity associated with healing and medicine in ancient mythology. This symbol carries deep meaning:

- The serpent, which sheds its skin, represents renewal, transformation, and the cyclical nature of health and life.

- The staff symbolises authority, stability, and support in the medical profession.

It is crucial to recognise that even positive portrayals of snakes can have unintended negative consequences, often leading to exploitation. In parts of Asia, there’s a traditional belief in the healing properties of snakes, contrasting with the ominous symbolism often conveyed by popular culture. This belief has given rise to practices such as the creation of snake wines, where whole snakes are steeped in alcohol, purportedly conferring medicinal benefits. Cobras, in particular, are frequently targeted for these purposes due to two main factors: the perceived medicinal properties of their venom and the potent energy they are believed to emit.

Regrettably, the sight of a fully-hooded cobra preserved in a wine jar has become a popular tourist souvenir, further exacerbating the issue. This cultural and medicinal significance has unfortunately placed considerable pressure on cobra populations (Read more about the above from the following two articles: BBC and Geographical).

Thus, the solution isn’t about portraying them in more positive light either, especially in symbolic manners. Solutions to change our perceptions of snakes have to be scientific, understanding a little about human psychology as well as scientific knowledge of wildlife.

Understanding Our Emotional Response towards Snake Encounters – Fight, Flight, Freeze and Fawn

Fear indeed plays a vital role in our survival instincts, especially when it comes to potentially dangerous animals like snakes. It’s a natural response that has evolved over time to keep us safe by triggering certain reactions – Fight, Flight, Freeze, or even Fawn – at varying levels of intensity.

These instinctive responses, collectively known as the stress response or acute stress response, are our body’s automatic physiological reaction to perceived threats. When encountering a snake, for instance, our brain rapidly assesses the situation and initiates one or more of these responses:

- Fight: Preparing to confront the threat directly.

- Flight: Readying the body to flee from danger.

- Freeze: Becoming immobile, often in hopes of avoiding detection.

- Fawn: A less commonly discussed response involving appeasing or submitting to the perceived threat.

The intensity of these responses can vary based on factors such as the individual’s past experiences, knowledge about snakes, and the specific context of the encounter.

Flight is often a standard response for many people when encountering snakes. Some individuals may instinctively run away, while others might take a few cautious steps back. When combined with ‘Freeze‘ response, individuals may observe and appreciate wildlife safely even when the snake is venomous as the snakes do not feel threatened. When faced with unknown snakes or any wildlife, whether in their natural habitats or unexpectedly in urban environments, maintaining a safe distance is a conscious manifestation of the flight response.

This precautionary behaviour is particularly crucial for those who lack expertise in snake identification or knowledge of their behaviour. In such situations, a rational fear serves as a protective mechanism, preventing us from approaching potentially dangerous animals too closely.

This measured response allows us to respect the animal’s space while ensuring our own safety. It’s a balanced approach that acknowledges our instinctive fear while allowing for a more controlled reaction, promoting safer interactions between humans and wildlife in various settings.

The fight response is often evident when humans encounter a pack of wild dogs. I have observed others and personally responded in similar ways – not to attack the dogs directly, but rather to make ourselves appear louder and more aggressive, with the hope of deterring the dogs. This behaviour typically involves raising our voices, making ourselves appear larger, and maintaining a confident posture, all while internally feeling quite nervous and apprehensive.

This response is a classic example of how our instinctive fight mechanism can manifest in a more controlled, strategic manner. Instead of engaging in physical combat, we attempt to intimidate and discourage the perceived threat. It’s a delicate balance between asserting dominance and avoiding direct confrontation, all while managing our own internal fear and stress.

While fight can serve as a protective mechanism, excessive or uncontrolled fight response can lead to unnecessary harm – both to humans and wildlife. Recent incidents in Singapore highlight this issue, where reticulated pythons were killed despite posing no immediate threat (see link). These tragic outcomes often stem from misunderstanding and a misplaced ‘fight’ response when individuals may feel compelled to eliminate perceived threats. This behaviour, while rooted in our survival instincts, often results in needless conflict and harm.

Sometimes, the fear driving these actions isn’t directed at the animals themselves. For instance, it may be a fear of social perception – a concern about how others might view us if we don’t take action. Questions like “Will I be seen as a coward or incompetent or unmanly if I don’t attempt to move closer, catch or kill the snake?” can lead to unnecessary aggressive behaviour towards wildlife and/or endanger themselves.

Fawning behaviour, whilst more commonly discussed in human psychological contexts, can indeed occur during wildlife encounters. In the context of wildlife interactions, fawning can be understood as attempts to appease or placate a perceived threat through submissive or “friendly” behaviours.

Common manifestations when it comes to wildlife encounters include offering food, avoiding eye contact, and speaking in a soft or soothing voice. However, these actions often stem from misconceptions and anthropomorphism, and can lead to risks. Offering food, for instance, is generally discouraged by wildlife experts as it can lead to habituation, altering animals’ natural behaviours and potentially harming their health. Moreover, it may increase the likelihood of aggressive encounters as animals learn to associate humans with food.

It is also important to note that fawning behaviours may be perceived as appeasing to one animal (maybe your specific pet dog or cat) could be seen as threatening to another. For instance, attempting to speak softly and gently with empathy to a fully-hooded Equatorial Spitting Cobra would be an extremely foolish, dangerous and misguided approach. This venomous snake’s defensive posture indicates it feels threatened, and any attempt at close interaction could result in a potentially life-threatening encounter. For snake encounters, wildlife experts generally advise against any form of fawning behaviour, instead recommending maintaining a safe distance and slowly backing away if necessary, which are both manifestations of flight behaviours.

Calibrating Fear via Education & Self-Management

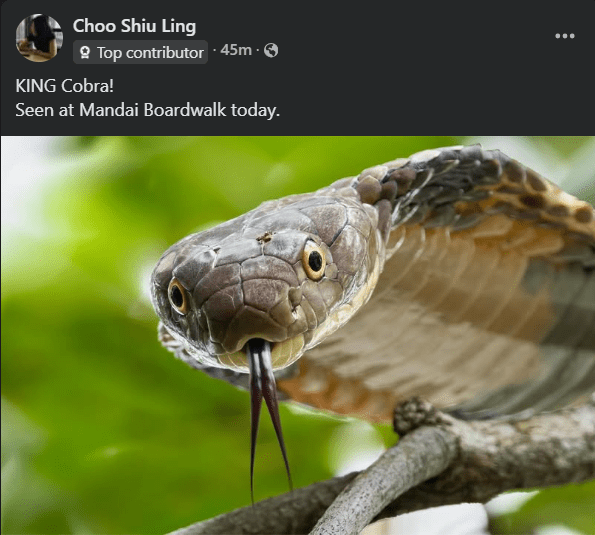

Intervention and preventive strategies for managing human-wildlife conflicts are becoming increasingly significant as occurrences have risen substantially over the years. This trend is driven by several factors: habitat encroachment, heightened awareness of mental well-being benefits from nature exposure, including ‘forest bathing’ and increased human comfort in venturing into wilder nature spaces. In fact, while typing this blog post, a nature enthusiast, Choo Shiu Ling and a few other photographers spotted and photographed a beautiful specimen of the highly venomous King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) along the newly opened Mandai Boardwalk on the 26th Jan 2025.

A recent Channel NewsAsia (CNA) report highlighted a significant increase in cases of animals entering urban areas in 2024, with wildlife management firms reporting a 65% rise compared to 2023. Common palm civets and long-tailed macaques form the bulk of these encounters.

To reduce human-wildlife tensions, I believe we need a two-pronged approach: education and self-management, targeting two parts of our human brain – the Prefrontal Cortex and the Amygdala.

Education is crucial as it provides knowledge that helps humans think and make decisions more rationally using our ‘top-brain’, specifically the prefrontal cortex, in wildlife encounter situations. This is achieved by learning about animal behaviour and responding with appropriate actions, such as maintaining a safe distance from animals or refraining from using pesticides against bronzebacks or other snakes encountered in one’s house. Anbu’s true story illustrates this point: one of her rescues involved a bronzeback that had been sprayed with pesticide. Fortunately, it was nursed back to health, unlike many other snakes that didn’t survive due to neurological disorders caused by such sprays.

Education about wildlife doesn’t require comprehensive knowledge, as not everyone will share the same level of interest. Instead, it’s about developing awareness and understanding key principles. This includes recognising when to step back, consciously walk away, or call a helpline when faced with unfamiliar wildlife situations. By adopting this approach, we ensure safety for both humans and animals whilst fostering more informed and compassionate interactions with nature.

One key knowledge to be equipped with is that most snakes are not ‘aggressive’ towards humans unless provoked or threatened. As Anbu humorously remarked during her “Snakes of Singapore” presentation, in her many years of snake rescues, she has been the one chasing after snakes rather than the reverse. In addition, she stressed that the more accurate term to describe a snake’s behaviour when confronted is “defensive” rather than “aggressive”. This distinction is crucial for understanding snake behaviour. Snakes typically react defensively when they feel threatened or cornered, rather than actively seeking confrontation with humans. Their primary instinct is to avoid conflict and escape potential danger. This defensive posture is a natural survival mechanism, not an indication of inherent aggression towards humans.

Another knowledge is recognising snakes’ vital role in the ecosystem. They help control rodent populations (which can be quite a severe problem in Singapore), and some, like our native King Cobras, even prey on other snakes, thus maintaining ecological balance. Understanding these important functions can help shift our perceptions from fear to appreciation of these remarkable creatures.

During my own nature walks over the years, I’ve also observed that most snakes tend to avoid human presence unlike how popular culture has typically portrayed them. However, there are notable exceptions, particularly among (semi) arboreal species. Two such examples are Wagler’s Pit Vipers (Tropidolaemus wagleri) and Reticulated Pythons (Malayopython reticulatus). These snakes often remain curled up on trees or man-made structures, appearing indifferent to their surroundings. Their behaviour is characterised by seeming sluggishness and prolonged periods of motionlessness. It’s important to note that this apparent inactivity is not just a sign of indifference but a key part of their hunting strategy. This stillness allows them to effectively ambush unsuspecting prey. If you become aware of these snakes’ presence, it’s advisable to maintain a safe distance. Despite their seemingly passive demeanor, they may still strike defensively if they feel threatened. Always prioritise your safety and respect the snake’s space when encountering these fascinating creatures in their natural habitat.

However, education alone is not sufficient. Self-management is equally important, particularly in regulating our immediate emotional reactions to wildlife encounters. The amygdala, a part of our brain responsible for processing emotions and triggering the ‘fight, flight, freeze, fawn’ response, plays a crucial role in these situations. This is especially challenging for individuals who may have had prior negative encounters with wildlife and as a result, developed ingrained perceptions towards specific animals due to traumatic incidents.

In such cases, responses can become more extreme due to what is known as an amygdala hijack – an intense, immediate emotional response that’s disproportionate to the situation. This occurs when the amygdala, the brain’s emotional centre, takes control and overrides the rational part of the brain, leading to potentially harmful or unnecessary reactions to wildlife encounters.

By practising self-management techniques (like regulating our breathing, learning to sit on moments of discomfort before going into our instinctive behaviours and pausing our instinctive response), individuals can learn to recognise and mitigate these amygdala hijacks, allowing the prefrontal cortex – responsible for rational thinking and decision-making – to guide behaviour instead. This approach helps regulate emotional responses, enabling more informed and measured reactions during wildlife encounters, ultimately protecting both humans and animals. At this juncture, I would like to share one of my favourite quotes, which I find very meaningful when it comes to self-management.

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response”.

— Viktor E. Frankl

In my opinion, by adopting this dual approach (which I admit is easier said than done), we can foster a more harmonious coexistence between humans and wildlife. It not only reduces unnecessary fears and conflicts but also promotes conservation efforts by encouraging more positive and informed interactions with local fauna. Ultimately, this strategy equips us with both the knowledge and the emotional regulation necessary to navigate human-wildlife interactions more effectively.

Lastly, wishing you a prosperous and auspicious Chinese New Year in the Year of the Snake. May the coming year bring you good fortune, health and happiness!

Written by Lucas Teo