Introduction

Allow us to introduce ourselves in a rather unconventional way. I’m Homo sapiens lucasensis trisilva, but you can call me Lucas Teo – that’s my ‘common name’. And joining me in this birdbrain adventure is my partner-in-crime, Homo sapien Gabriellus auricomus agaricus, better known as Gabriel Kang. Curious about Gabriel’s quirky scientific name? Check out his profile picture on his instagram i.e. gabriel.birdbrain (Hint: Google the meaning of auricomus and agaricus).

Anyway, here’s a thought experiment: try Googling “Lucas Teo” or “Gabriel Kang”. How many results do you get? Quite a few, I’d wager. This little exercise brings us to an intriguing question: Why do scientific names matter?

The Challenge of Common Names

Common names, while convenient for everyday use within the same geographical area, culture and language, may lead to confusion and ambiguity in scientific contexts when applied across cultural and political boundaries.

Let’s consider the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) as an example. This striking blue and orange bird, found across Eurasia, is known by several names in English alone:

- Common Kingfisher

- Eurasian Kingfisher

- European Kingfisher

- River Kingfisher

- Small Blue Kingfisher

This diversity of names within a single language demonstrates the potential for confusion in scientific communication. The situation becomes even more complex when we consider names in other languages and cultures. For instance, in French, it’s known as “Martin-pêcheur d’Europe”, while in German, it’s called “Eisvogel” (ice bird). In Chinese, it’s fondly referred to as “Xiao Cui” (小翠). Such linguistic and cultural variations highlight the need for a standardised naming system in scientific contexts.

When the Common Names Mean Different Things in Different Countries

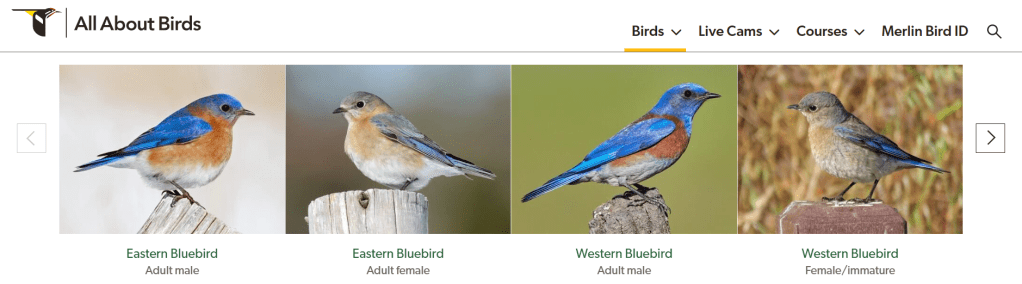

Many common names are based on physical descriptions, which can lead to further confusion. For instance, “bluebird” might refer to several different species across various families. In North America alone, there is a Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana) and a Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides)… and I believe there is also a Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis)?

While these birds share a similar blue colouration, they are distinct species with different hunting styles (though with many other similar behaviours and traits). Moreover, other blue-coloured birds like the Blue Grosbeak (Passerina caerulea) or Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) might also be mistakenly called “bluebirds” by casual observers.

To further complicate matters, the term “bluebird” isn’t limited to North American species. In Singapore, we have our own Asian Fairy Bluebird (Irena puella), a strikingly beautiful bird with vibrant blue plumage. Despite its common name, this species is not closely related to the North American bluebirds. It belongs to a different family altogether (Irenidae) – related to leafbirds, while the North American bluebirds are members of the thrush family (Turdidae).

This example illustrates how common names can be misleading across continents. A birdwatcher familiar with North American bluebirds might be quite surprised to encounter the Asian Fairy Bluebird, which has a different appearance, behaviour, and ecological niche.

This issue extends beyond birds. The term “silverfish” is used for a specific insect (Lepisma saccharina), but can also represent the Antarctic silverfish (Pleuragramma antarctica), also known as the Antarctic herring – a true fish that swims in the sea. This example further illustrates how common names can lead to confusion across different animal groups, potentially causing misunderstandings in scientific discourse.

These examples highlight how common names based on physical descriptions can be misleading, as many different species may share similar physical features. This is where scientific names become invaluable.

When the “Common” May Not Be Common

Sometimes, we see the adjective “common” being used to describe a bird or other aspects of the nature world. It may be misleading like a misnomer. I will be sharing two examples to illustrate this point i.e. the Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis) as well as the Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis).

The use of the adjective “common” to describe birds or other aspects of the natural world can sometimes be misleading or act as a misnomer. Two examples that illustrate this point are the Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis) and the Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis).

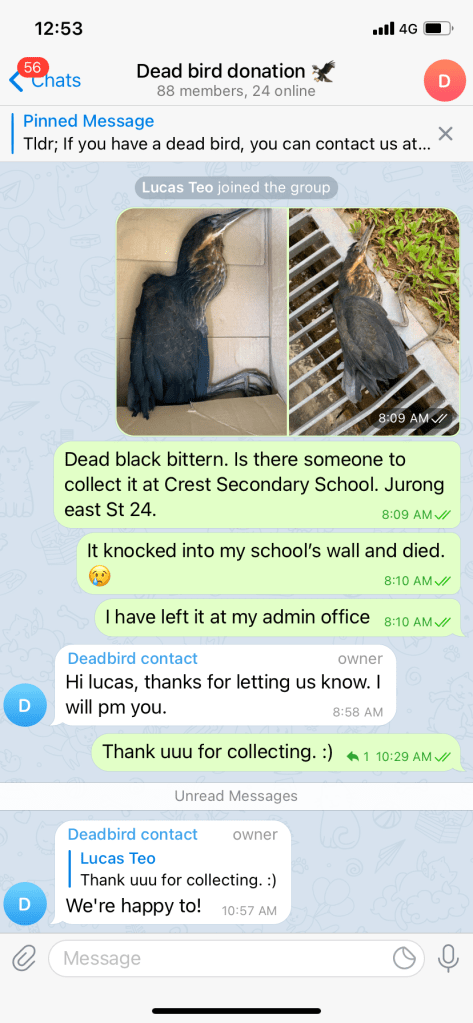

In the context of Singapore, the Common Myna is ironically no longer commonly seen, despite being a native species known for its high adaptability to urban environments. This decline is primarily due to the introduction of the Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus), a species originating from Java, an island in Indonesia in the 1920s. The Javan Myna has outcompeted its “common” counterpart, likely due to its superior ability to exploit limited nesting cavities in urban structures and trees. This competition has caused the Common Myna’s population to decrease significantly in Singapore. In fact, it is likely that the Javan Myna is the most common bird in Singapore right now. You may refer to this very comprehensive article from Bird Ecology Study Group to understand reasons behind their ubiquitous presence.

This example highlights how the term “common” in a species’ name may not always reflect its current prevalence in a given ecosystem, especially when factors like introduced species and habitat changes come into play.

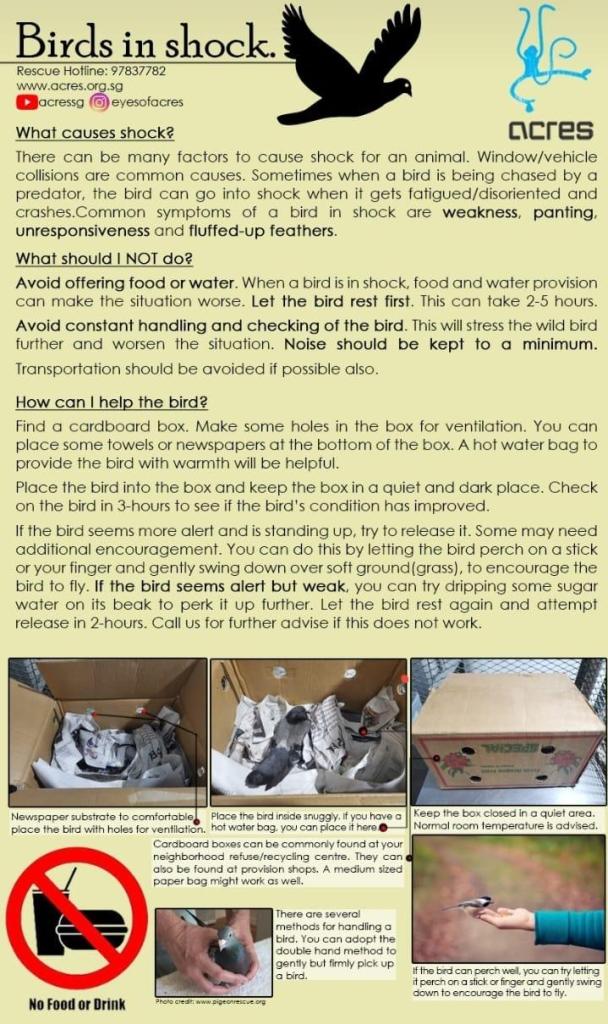

During the migratory season, one of the kingfisher species that arrives in Singapore is the Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis). Despite its name, this bird is not commonly seen in Singapore, even during migration periods. The term “common” in its name refers to its prevalence in its native range, not its abundance in Singapore.

In contrast, the most frequently observed kingfishers in Singapore are:

- The Collared Kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris)

- The White-Throated Kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis)

These observations, based on local birding experiences, highlight how the word “common” in a species’ name can be misleading when applied to different geographical contexts.

When Descriptors in Common Names Aren’t Unique

Two species of bee-eaters found in Singapore, the Blue-Tailed Bee-eater (Merops philippinus) and the Blue-Throated Bee-eater (Merops viridis), serve as excellent examples to illustrate why common names can sometimes be problematic for bird identification.

Both species actually have blue tails, which makes the “Blue-Tailed” descriptor in the common name of Merops philippinus potentially confusing. This shared characteristic demonstrates how common names can sometimes fail to highlight distinguishing features between similar species.

The key difference between these two bee-eaters lies in their throat colouration:

- The Blue-Tailed Bee-eater (Merops philippinus) has a chestnut-coloured throat.

- The Blue-Throated Bee-eater (Merops viridis), as its name suggests, has a blue throat.

This example highlights the importance of looking beyond common names when identifying birds. For instance, considering the time of year can be crucial, as Blue-Tailed Bee-Eaters are not present in Singapore during the non-migratory season. More specifically, in this case, examining the throats of both bee-eaters provides a more reliable distinguishing characteristic.

Whilst common names can be helpful, they may not always capture the most distinctive features of a species, especially when comparing closely related birds. By focusing on these specific details, birdwatchers can more accurately identify and differentiate between these similar species, regardless of potentially misleading common names.

The Binomial Nomenclature

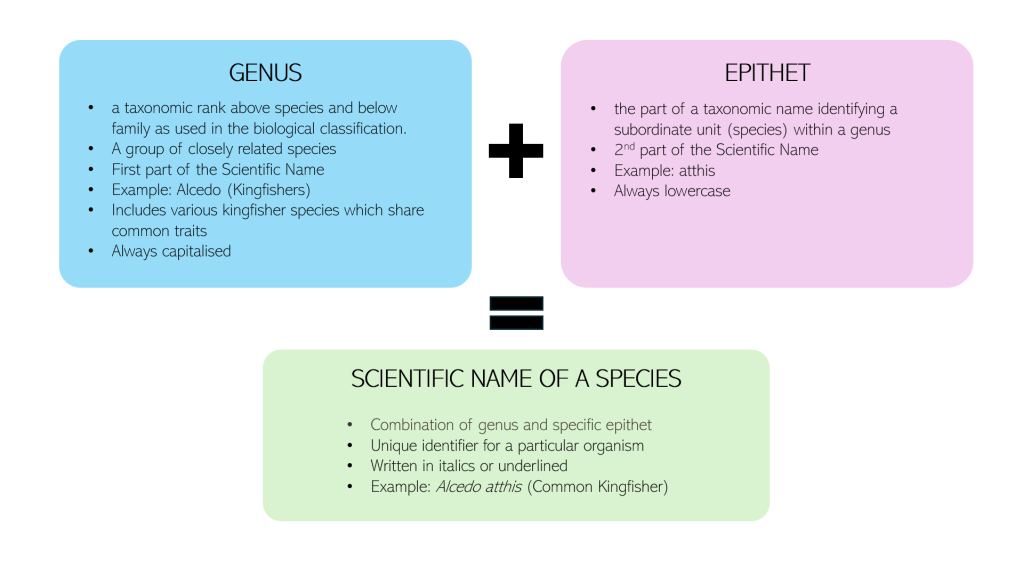

Scientific names provide a standardised system recognised globally. The scientific naming system indeed consists of two main components, described as:

- Genus (e.g., Alcedo): Represents a group of closely related species. It is the generic name of the species.

- Specific epithet (e.g., atthis): The second part of the scientific name that, together with the genus, identifies the specific organism. It is the specific name of the species.

The term ‘species name’ in scientific contexts refers to the complete scientific name, which is the combination of the genus and the specific epithet. This system is known as binomial nomenclature. In the case of the common kingfisher, Alcedo atthis, ‘Alcedo‘ is the genus and ‘atthis‘ is the specific epithet. Together, they form the species’ scientific name. This two-part system provides a unique identifier for each species within a genus, although the same specific epithet may be used in different genera. The genus is always capitalised, while the specific epithet is always in lowercase, and both are typically italicised or underlined when written.

Note: In some cases, scientists may use additional classification levels, such as subspecies, to denote distinct populations within a species or other taxonomic ranks to further classify organisms. However, the genus and species form the core of scientific naming.

The Importance of Scientific Names

Scientific names serve several crucial functions in biological research and conservation:

- Precision in Communication: They provide distinctions between species of the same genus (which causes them to have similar characteristics), such as the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) and the blue-eared kingfisher (Alcedo meninting), or between the North American bluebirds (Sialia spp.) and the Asian Fairy-bluebird (Irena puella).

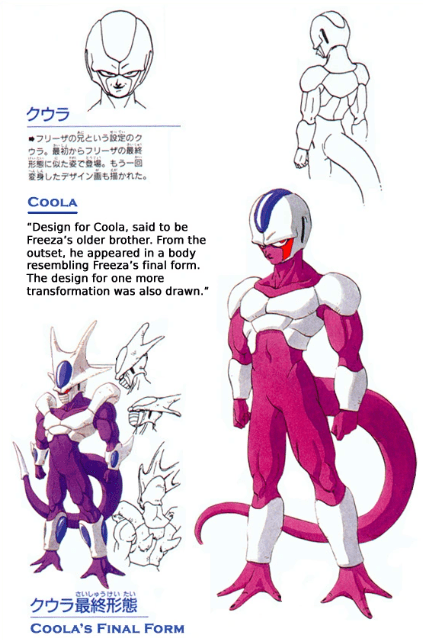

- Evolutionary Understanding: These names reflect our current understanding of species relationships and evolutionary history. The first part of a scientific name, the genus, groups closely related species together. For example, between Homo sapiens (modern humans), Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthals) and Homo erectus (an extinct human species), all these species share the genus Homo, indicating that scientists believe they are closely related and share a recent common ancestor.

- Overcoming Descriptive Limitations: Unlike common names, scientific names are not entirely based on overly simplistic physical appearances, which can be deceiving. They provide a unique identifier for each species, regardless of how similar the species may look to others.

The Human-Cultural Element in Scientific Naming

While scientific names are primarily functional, they occasionally reflect human creativity, humour, and even diplomacy. For instance, the Spongiforma squarepantsii: A mushroom species named after the cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants.

In another instance, a moth species, Neopalpa donaldtrumpi, as you can see, is named after President Donald Trump due to its golden scales on its head that looks like the president’s hair colour and style (Read this article for more details).

An intriguing example of the intersection between scientific naming and diplomacy can be found in Singapore’s practice of naming new orchid hybrids after visiting political leaders or important figures. This tradition, known as “orchid diplomacy”, began in 1957 and has since become a significant honour bestowed upon state visitors.

For example:

- Dendrobium Memoria Princess Diana: Named in memory of the late Princess of Wales

- Dendrobium Barack and Michelle Obama: Named after the former U.S. President and First Lady

This practice not only showcases Singapore’s rich botanical heritage but also creates a lasting scientific legacy of diplomatic visits. Each of these specially bred hybrids receives a unique scientific name, following the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, while also carrying the name of the honoured guest.

These examples demonstrate how scientific naming can transcend mere classification to become a form of cultural expression, historical record-keeping, and even a tool for international relations.

Conclusion

Scientific names, whilst some of us find challenging to pronounce, serve as a universal language in the natural sciences. They provide precise identification, facilitate global communication among researchers, and offer insights into evolutionary relationships. Most importantly, they overcome the limitations of common names, especially those based on potentially misleading physical descriptions.

Whether it’s Homo sapiens, Alcedo atthis, Irena puella, or Spongiforma squarepantsii, each scientific name encapsulates a wealth of information about an organism’s identity and place in the vast tapestry of life. As we continue to explore and understand the biodiversity of our planet, the importance of this standardised naming system becomes increasingly apparent.

The next time you encounter a scientific name, consider it not just as a label, but as a key to unlocking a deeper understanding of the natural world. And let’s be honest, there’s a certain satisfaction in being able to remember and pronounce these names correctly among your fellow nature enthusiasts. It’s not about feeling superior, but rather about sharing a common language that connects us to the fascinating world of biodiversity.

Nevertheless, while scientific names are crucial for precise identification and communication in academic and professional settings, common names still have their place. For hobbyists and enthusiasts, using familiar, local names in casual conversations is perfectly acceptable and often more practical.

Written by Lucas